THE SCIENCE OF ASTRONOMY IS BASED ON THE PHYSICAL CONSTITUTION OF THE UNIVERSE.

In order to explain from what principles we get our judgements of its movements, we must first acquire a thorough understanding of the nature of those motions.

Many people believe that the solar system has a roughly spherical form.

This isn't the case at all.

It's a flat disk, to put it that way.

It spins in a single plane.

The planets veer away from this plane, albeit just a smidgeon.

The question of how this situation came to be has long been a source of debate in astronomy, and it has yet to be fully resolved.

However, the basic notion is that there was once a huge burning mass rotating in space-we don't know why or how.

Certain heavier parts of the body accumulated over time due to gravity, and this mass, being cohesive, was thrown out, maintaining its general movement in space but having a revolutionary movement of its own in the same plane.

This body eventually constricted and solidified as it continued to radiate heat into space.

The planet Neptune was the first body discovered.

The similar process occurred many times, resulting in the formation of Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, asteroids, Mars, the Earth, Venus, and Mercury.

Many more bodies were created in the same manner, but they lacked the principle of coherence to the same extent, and shortly after separating from the Sun, they broke up into asteroids and meteors, of which there are countless millions in interplanetary space.

Furthermore, some of these things acted at first like the Sun itself, ejecting smaller bodies of the "moon" type.

These were tiny compared to the current sphere, cooled rapidly, and lost their internal revolutionary action.

The Earth's Moon, for example, continues to orbit around the Earth but no longer rotates on its own axis, and constantly shows the same face to us.

All of this is essential because all of these movements—complex as they are (and we haven't attempted to explain that intricacy in full, just to provide a rough idea)—take occur on one thin plane with two major directions.

The discovery of Neptune is well-known among astronomy students.

Certain disturbances were found when calculating Uranus' motions that could not be explained by any of the known planets.

As a result, astronomers were led to believe that there could be another body beyond Uranus that had yet to be found.

Calculations were then performed to estimate the likely location of such a body, which was subsequently sought out with great care, and eventually Adams and Le Verrier identified the boundaries of its potential position with such precision that Galle of Berlin found it in 1846.

Neptune's position as the furthest planet is far from definite.

Further observations and computations reveal that some Uranus motions are still unaccounted for by Neptune, as well as disturbances in Neptune himself 4suggesting the existence of another planet beyond Neptune.

If that's the case, the distance is very certainly enormous.

Our reasoning is based on Bode's Law number five.

Bode was a German astronomer who lived in the latter half of the 18th century and the first quarter of the 19th century, and his law is as follows: The distance of Mercury from the Sun in astronomical units is calculated by dividing 4 by 10, with the Astronomical Unit being the mean distance between the Earth and the Sun.

We get the distance of Venus by adding 4 to 3 and dividing it by 10; we get the distance of Earth by adding twice 3 to 4; we get the distance of Mars by adding twice twice 3 to 4; and we get the mean distance of the asteroids by adding twice twice twice 3 to 4.

We obtain the mean distance of Jupiter by multiplying 3 four times by 2 and adding it to 4, then dividing by 10.

Multiplying 3 by 2 again yields the distance to Saturn; multiplying 3 by 2 again yields the distance to 1 Uranus.

The legislation, however, does not apply to Neptune.

The mean distance should be 38.8 according to that rule, yet it is only 30.

This rule has no clear explanation, but it is anticipated that future study into celestial mechanics and the development of the solar system may shed some light on the topic.

At the very least, the rule was useful in that it led to the discovery of asteroids, which are thought to represent the remains of an exploding planet.

There has been no acceptable explanation for Neptune's exception to this rule.

The fixed stars now orbit the Sun at enormous distances, far beyond the reach of even the most distant planets.

It is difficult for the human intellect to comprehend the vastness of space.

There is no region of the sky where these stars are not present; they fully encircle the Sun.

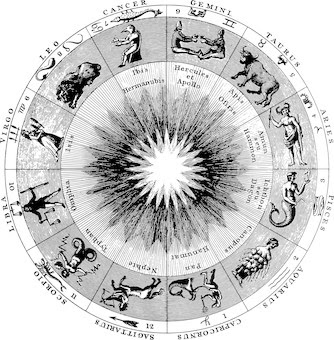

To return to the wheel analogy, if we look along the spokes of the wheel, we will see a narrow band of stars, which naturally arrange themselves into twelve constellations spaced at about equal distances.

We pay greater attention to these stars because they are in the same plane as the solar system's overall movement, and so their influence naturally blends with that of the planets.

Their effects have been meticulously researched and documented by ancient astrologers from time immemorial.

These constellations have been given names.

Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricornus, Aquarius, and Pisces are the zodiac signs.

The majority of the names are those of symbolic animals.

Trying to find any similarity between these creatures and the relative locations of the stars is a bit of a stretch.

The names were chosen because of their astrological importance, and this is one of many examples of how astrology predates astronomy.

The materialistic school of thought has attempted to create the appearance that we have some genuine understanding of the nature of the forces at action in our environment.

This is a completely incorrect perception.

All forces are inherently enigmatic.

We can tell how they behave based on observation, comparison, and measurement.

We can't even come up with a fair description of their actual personality.

Take, for example, the gravitational pull.

Men of science have been forced to hypothesize a material called the ether in order to explain its operation.

They were forced to put this ether into mathematical words.

It is endlessly hard, infinitely stretchy, infinitely flimsy, and infinitely ambiguous.

That is to say, it is not matter in any common meaning of the term, since it contains infinities of characteristics and therefore [is] more theoretical than real.

Similarly, no one understands exactly what electricity is.

There's a tale of a professor who was delivering a speech to this effect in front of a class of students and ended by shouting, "Does anyone know what electricity is?" Half asleep was a student at the rear of the hall, who had been overwhelmed by the heat or the discussion.

The final phrase jolted him awake, and he sprang from his seat.

When he met the professor's stern gaze, he felt embarrassed and muttered, "I know, sir, but I forgot." The educated guy replied, "It's just my luck." "Only one guy in the whole world knew, and he has since forgotten."

Even the most basic phenomena, such as the expansion of bodies due to the action of heat, is shrouded in mystery.

Because heat is thought of as a method of expression or accompanying attribute of motion, there is a notion that the molecules of a body move more violently when what is termed heat is given to them.

However, these molecules are just speculative.

Their existence was imagined in order to explain certain chemical activity occurrences.

These imaginary molecules are made up of even more imaginary atoms, which were once defined as ultimate indivisible particles of homogeneous matter, as the name implies; but that was only a century ago, and since then, all sorts of other phenomena have been observed, making it impossible to imagine the atom as indivisible any longer.

As a result, a new hypothesis, that of electrons, has emerged; and if you ask a physicist if these electrons constitute matter, he may tell you that, on the whole, the least implausible explanation is that they are simply ether strains.

In other words, science has resolved the things that are into combinations of things that aren't.

If you ask a contemporary chemist or physicist for his description of matter, he will respond in words that are almost similar to those used by Middle Ages philosophers to describe Spirit.

The astrologer is more forthright than other scientific professors.

He doesn't try to hide his ignorance under a garment of philosophical jargon that is intricately woven.

He is willing to accept the Schoolrnen's dictum, exeunt omnium in mysterium,l which means that if you pursue any concept far enough—if you keep questioning how, why, and what, rather than being satisfied with a superficial, half-baked explanation—the end conclusion is always the same.

You've reached the incomprehensible blank wall.

If there is anybody alive today who does not understand the importance of astrology and makes decisions only on the basis of materialistic criteria, let him read Herbert Spencer's First Principles.

He will find it shown with remarkable clarity in that work, which ranks with David Hume's as one of the most masterly treatises on nature as viewed by scientific skepticism, that no conceivable explanation of God or of nature is acceptable to the intellect.

Furthermore, he demonstrates that no such theory is even comprehensible to the intellect.

As practical people, we should thus avoid getting too caught up in metaphysics.

We'd be better off accepting the axiom that everything is relative and limiting ourselves to watching and quantifying the forces we see in operation.

Why does the movement of a particular planet generate certain results is not an argument against astrology?

We don't know why a nerve contracts when an electric current is applied, any more than a physicist understands why a nerve contracts when an electric current is applied.

We don't want to get into such a philosophical discussion.

We're just interested in knowing whether or if it acts.

In astrology, like in any other discipline, theoretical a priori assumptions must not be advanced.

Every science has suffered from such concerns.

They have slowed science's development more than any other kind of human stupidity.

On this subject, the reader should read T. H. Huxley's writings.

People used to start their conclusions from what they thought was irrefutable evidence of the characteristics of the Divinity.

When they came across a fact that contradicted their preconceived notions about His nature, they tried to explain it away, but since facts aren't beliefs that winna ding, they realized that their castle in the sky was crumbling, and they resorted to the expedient of burning anyone alive who appeared to be interested in the discovery of inconvenient facts.

Such a policy was, by definition, suicidal.

Now, astrology has nothing to do with any scientific ideas.

It follows the real scientific process, as does all rational science.

Assume we're on a shooting range and see a cloud of smoke followed by a report.

We hear a bell ring or see a flag wave nearly instantly in another area of the ground.

There is no reason to believe that these events are connected in any way.

It's possible that they're just coincidences.

However, if we witness the identical thing happen a hundred times in a row (or even if we see the flash and hear the shot a hundred times, with the waving of the flag on seventy or eighty of those instances), the situation changes dramatically.

We have every right to conclude that there is, at the very least, some causal relationship.

However, we would still be perplexed as to why a flash in one area of the Earth could cause a flag to be waved in another.

There would be nothing to indicate that the shooter and the marker had made a prearranged arrangement; even if we were later informed that this was the case, we would still be unsure of the motives for such an arrangement, and in order to discover these, we would have to delve into a dozen sciences, including ballistics, history, ethnology, and I'm not sure how many more.

At the end of it all, we'll be confronted with the big metaphysical issue that we've already rejected as implausible.

However, it would be reasonable for the observer to infer certain practical conclusions.

If he saw the flag being waved every time the shot was fired for a thousand times, he would be completely right in predicting that the next time the flash occurred, the flag would be waved as well.

This forecast, like any other, isn't guaranteed.

It would just be a very strong possibility, but mankind is used to acting on such probabilities.

If I go down Fifth Avenue, a vehicle may slam a wheel, slide, or otherwise cause an obstruction to my pleasant stroll along the sidewalk, but I would be a fool if I avoided the sidewalk for any reason.

To put it another way, I routinely forecast that no such mishap will occur.

So far, everything has turned out just how I had hoped.

When an astrologer forecasts that a person with Mars in the 7th House will have an unpleasant marriage, if he marries at all, he is using the same characteristics of good reasoning and judgment based on scientific observation and comparison of countless data.

He has watched, recorded, and calculated hundreds of horoscopes in which this position appears, and in every instance, the individual born with this position has been unlucky in marriage.

When he sees another similar figure, he is quite right in forecasting a failed marriage.

It is unrealistic to expect any respectable astrologer to claim to be completely correct. In the study of astrology, there are many complications.

It seems that there are unknown factors at work that may sway even the most likely decision.

There are instances, for example, when a person may go through very negative experiences without experiencing any negative consequences.

Those elements have not been energised to action for whatever reason.

There are a slew of ideas to explain this seeming anomaly.

It is difficult to go into detail about them in this short introduction, but there are so many and so delicate factors to consider that it is often impossible to discern astrologically why any particular event should occur, even when the issue is examined after it has occurred.

Another crucial thing to remember is that "forewarned is forearmed." If a person seems to be in danger of drowning, keep him away from the water as much as possible.

This is one of astrology's most helpful features.

It's possible that the astrologer is wrong, that the risk isn't as great as it seems, but it can't hurt his client to behave prudently, and every competent astrologer is full of worldly knowledge and common sense.

These factors are especially relevant in horary consultations, when the astrologer is sought for help with an urgent worry or problem; the consultant's natural excellent judgment is interfered with by the disturbance of his mind at such times, and the astrologer's advice can only be helpful.

However, it would be foolish to dismiss the astrologer's claim to be able to assist humanity.

The probability of cause and connection is so great on certain major points, such as the relationship between personal appearance and the sign rising at the time of birth or the position of the Sun in the zodiac, the influence of Saturn in the 10th House or Mars in the Ascendant, and a thousand others, that no sane person studying the facts with intelligence and without prejudice can fail to notice it.

The initial vapors that come over in fractional distillation have a very different character than those that come over when more heat is applied, and the sequential creation of the planets has given them quite distinct natures.

The delicate impact that their beams detach from them and shed on Earth has been researched in depth, and will be explained in this book.

There's nothing especially irrational about accepting such a notion.

The obvious comparison may be found in well-known physics departments.

We are all familiar with the difference in effect generated by the Sun's and Moon's beams, and all we have to do now is expand this idea to include the other planets.

However, adopting the premise that the planets' aspects have any influence is problematic from the start.

Let us think about this for a moment.

What do we mean by the planets' aspects in the first place?

The angle subtended by any two planets at the observer's sight is the aspect of one to the other.

The Sun is in opposition to the Moon when the Moon is full, which means that if a straight line were drawn from the Sun to the Earth and produced, it would pass through the Moon.

We now know that this specific feature has an effect on Earth, and that this effect is related to the force known as gravity.

When the Sun and Moon are in opposition, they pull in opposing ways, creating a balancing.

As a result, the Earth is not pushed out of shape as much as when they are in tandem and tugging together.

The tides are used to measure the impact, however this is not the doctrine of the aspects.

These pressures operate at a progressively decreasing angle as the Moon moves away from its full phase, and their influence on the tides likewise decreases in a steady and proportionate manner.

The astrological influences are completely ineffective in this situation.

The impact is created at the precise moment of opposition.

It ceases to exist as soon as it is fifteen or twenty degrees away, and it is difficult to understand why this is true from a philosophical perspective.

Let's suppose Mars reaches Uranus' square, and a massive earthquake occurs.

A week later, the aspect has gone, and we are experiencing no earthquakes at all, not as one would expect.

One may be inclined to dismiss this as irrational, and it has been used as a counter-argument against astrology.

Fortunately, in the science of optics, we have a pretty excellent parallel.

Put on a pair of field glasses and gaze out the window at the landscape—all it's blurry.

When you move the screw back and forth, the blurring becomes a little worse or better, but there is one specific position of those glasses that is unique to their relationship with your own optic lenses, where the picture suddenly becomes clear and bright.

A glass is either in focus or out of focus, and although a small deviation causes less blurring than a bigger one, the line of demarcation is absolutely crisp.

Other parallels include the phenomena of water boiling; water does not boil at 99° C, but it does boil at 100° C, and there is a greater physical difference between the water at 99° and the water at 100° than between the water at 99° and the water at 10.

However, we don't understand why the planets' rays only interact with each other and mix their actions when they hit the Earth at certain angles.

The science of astrology is mainly empirical at the moment.

We know that some occurrences on Earth correspond to particular celestial alignments.

We have seen these occurrences so many times that we are certain there is a reason and link between them, yet no astrologer claims to know what that connection is.

The reader will recall that David Hume, who has never been contradicted, considered causation to be not only unproven and unprovable, but also unimaginable.

The Causalists were a school of thinkers who believed that every event was the result of the Deity's direct will.

The apple detaches from the tree and falls to the ground for two reasons: first, God wants the fruit to detach from the tree; second, God wants the apple to fall to the ground.

They argue that asserting that one consequence must inevitably follow another is not only unphilosophical, but also blasphemous, since it limits the Creator's authority.

It is difficult to refute this viewpoint with reasoning, no matter how repulsive it is to our common sense.

The importance of indicating the possibility of such a position is to demonstrate that, from a purely rational standpoint, the assertion that high tides are linked to the new Moon is just as absurd as-not more absurd nor less absurd than-the assertion that the conjunction of Saturn and Mars is bad for empires.

If there is any difference in logical quality between these two statements, the logician who can discover it has yet to be born.

If we accept one more easily than the other, it is because it is based on more widespread observation; nevertheless, it is entirely empirical, and the fact that we have a lovely theory to account for it in no way diminishes the original credit it deserves.

Perhaps the reader recalls Charles II asking the Fellows of the Royal Society why, if you filled a bowl of water to the brim, you could put a live goldfish in it without spilling it, but if the goldfish was dead, the water would instantly overflow.

They conferred on the subject and fought vehemently over it in the style of metascience, eventually coming to the "merry king" with nine erudite and acceptable answers.

It had never occurred to any of them to test if the king's assertion was true via experimentation.

The creation of hypotheses has been a tremendous burden to science at times.

The inclination is to extrapolate from a lack of evidence and, after a theory has been formed, to reject or ignore any facts that do not instantly fit into it.

Immanuel Kant's showing that the so-called laws of nature are, in fact, simply the rules of the mind is one of the most valuable contributions to thinking ever made.

It's not true that two plus two equals four; it's only that we're forced to believe it.

The implications of this are crucial in astrology.

More human observation is needed in astrology—a lot more human observation.

The astrologer is forced to reason from data that is often incorrect and, in some cases, intentionally fabricated.

In a nutshell, he's supposed to build bricks without straw.

It is therefore immensely to his credit that he has created such a magnificent pyramid of truth.

In this book, the approach will be completely scientific.

Facts were gathered, chosen, and coordinated, and conclusions were made from them with the strictest respect to the canons of truth, scientific method, and logic principles.

Every assertion is founded on centuries of collected experience as passed down via tradition and treatise, and the basic information so gained has been sifted repeatedly by applying the tests of proof that accumulate everyday in private study.

It isn't claimed that such information is complete.

It is conceivable that new facts will be found at any time, changing the previously held beliefs.

The discovery of Uranus and Neptune, for example, have had a significant impact on astrology.

Many of the ancient astrologers' concerns were addressed as a result of such occurrences.

In astrology, there are still many unresolved issues.

To give you an example, consider the following: Jupiter's transit through the 4th House may result in an inheritance.

Four out of five times in a man's life, this may occur with extreme regularity; the fifth time, no.

Why? There may be a slew of ideas.

None of them could possibly satisfy the intellect.

However, it is possible that the finding of yet another planet will provide a clear and apparent answer.

Astrology occupies the same status as all other sciences.

There is a lot that is known, but there is also a lot that is unknown.

It at least compares to all other sciences in terms of its adherents' dedication and competence, as well as their acuity and intellect, and their desire to make the practical advantages of their own knowledge available to every member of the human species.